|

Case Report

Deep wound infection caused by Enterococcus raffinosus in a below-knee amputation: A rare post-surgical complication

1 Western Reserve Health Education, 1350 E Market St, Warren, OH 44483, USA

Address correspondence to:

Marielle Roberts-McDonald

Ross University School of Medicine, 10315 USA Today Way, Miramar, FL 33025,

USA

Message to Corresponding Author

Article ID: 100017Z16MM2025

Access full text article on other devices

Access PDF of article on other devices

How to cite this article

Roberts-McDonald M, Brooker M, Mansur S, Vitvitsky E. Deep wound infection caused by Enterococcus raffinosus in a below-knee amputation: A rare postsurgical complication. J Case Rep Images Infect Dis 2025;8(1):1–4.ABSTRACT

Enterococcus species are commonly associated with nosocomial infections including urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and endocarditis. Enterococcus raffinosus is rarely diagnosed; however, it has been reported more recently over the last few decades. The case presented below illustrates a rare wound infection with positive wound cultures for E. raffinosus in a 68-year-old male with significant comorbidities and recent surgeries. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential due to the high mortality rate associated with this bacterium. When considering deep wound infections, E. raffinosus should be considered on the differential when determining the management of these patients.

Keywords: Deep wound, Deep wound infection, Enterococcus raffinosus, Enterococcus species, Post-surgical complication

Introduction

Enterococcus species are a gram-positive facultative anaerobic coccus commonly associated with nosocomial infections. Among these, Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are the most common [1] with other rare species known including E. casseliflavus, E. gallinarum, and E. raffinosus [2]. Urinary tract infections, bacteremia, and infective endocarditis are the most commonly associated with the Enterococcus species, with rare reported cases of intra-abdominal infections and meningitis [3]. They are highly resilient species that can survive in a variety of conditions, including treatment with common antiseptic and disinfectant agents [3].

Reports of Enterococcus raffinosus (E. raffinosus), a non-motile, catalase-negative, raffinose-positive, facultative anaerobic bacteria, began over the past two decades [1],[2]. This bacterium species is the leading cause of nosocomial infections due to its widespread antibiotic and multidrug resistance gained over the last several years [1],[2]. Cases of E. raffinosus specifically have been described primarily in bacteremia, endocarditis, as well as reported in sinusitis, decubitus ulcer, vertebral osteomyelitis, vaginal infection, endophthalmitis, and urinary tract infections [1]. E. raffinosus has also been recovered from urine specimens and wound swabs, however, there is no literature published to confirm the ability of E. raffinosus to cause serious invasive disease [4]. A wide range of symptoms have been reported depending on the clinical diagnosis with positive culture for this bacterium; however, there are no clinical features specific to E. raffinosus [3],[4]. Of all enterococcal bacteremia events, only 0.6% are reported positive with E. raffinosus bacteremia with less than a handful reported in the literature related to E. raffinosus deep tissue wound infections [5].

We present a case of a 68-year-old male with pertinent past medical history of recent admission for below-knee amputation (BKA) with wound wash out, who returned to the hospital for evaluation of purulent drainage from the wound site, with subsequent wound cultures positive for E. raffinosus.

Case Report

The patient was a 68-year-old male with past medical history of BKA five days prior, diabetes mellitus (DM), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), stem cell transplant in 2008, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), brought from a nursing facility, who presented to the ED for profuse purulent foul smelling drainage from his R BKA wound, and was admitted to the intensive care unit due to sepsis secondary to BKA wound infection. Two weeks prior, the patient underwent BKA wound washout and debridement with delayed primary closure. Wound cultures were ordered and the patient was treated with unasyn and discharged back to the nursing facility on augmentin. After discharge, the patient continued to display altered mental status/cognitive decline, decreased appetite, and urinary incontinence. This was a significant departure from his baseline as per nursing staff.

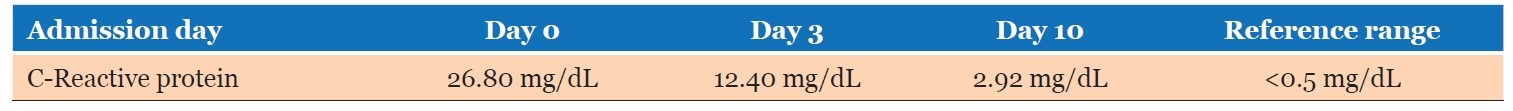

In the ED, the patient was disoriented, with significantly altered mental status, and hypotensive at 60/23 with a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 35. The patient was afebrile at 97.1 F, normal heart rate of 79 beats per minute, and normal respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute. The labs were significant for elevated white blood cells (WBCs) of 18.5 (trend seen in Table 1), lactic acid of 11.0, and C-reactive protein of 26.80 (trend seen in Table 2). Blood culture and wound cultures were ordered and obtained. Vascular surgery and infectious disease (ID) were consulted. The patient was started on intravenous (IV) Vancomycin and Zosyn for broad coverage and above-knee amputation (AKA) with wound vaccum-assisted colsure (VAC) placement was scheduled for the next day.

During R AKA procedure, an abscess cavity measuring 10 cm × 5 cm was identified tracking posteriorly to the femur. Acute purulent fluid drainage was noted, additional cultures were obtained, and the decision was made to perform guillotine amputation with wound vacuum-assisted closing (VAC) due musculature pallor. As there was no concern for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) growth, ID discontinued Vancomycin. Superficial wound cultures of BKA wound demonstrated Diphtheroid, mixed gram-negative rods, and Enterococcus species. Additionally, deep wound culture of the right lower extremity demonstrated mixed gram-negative rods, anaerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-positive rods, and E. raffinosus. Infectious disease recommended discontinuing Zosyn and adding Unasyn for additional six weeks to cover gram-negative bacteria. A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line was placed for administration of long-term antibiotics. The white blood cell (WBC) count continued to trend downward, stabilizing between 4.0–5.0 × 103/µL.

Finally, the patient returned to the OR approximately two weeks after admission to formalize the R AKA with delayed primary closure. Upon inspection of the site, the wound was free of necrotic tissue, non-viable tissue, and purulent drainage. The procedure was completed successfully with placement of 10 French Jackson–Pratt (JP) drain within the surgical stump. Jackson–Pratt drain output was monitored for a few days, then removed, and the patient was discharged back to his nursing facility for further management.

Discussion

Enterococcus raffinosus is not commonly recognized as part of the natural human bacterial flora and is rarely isolated from clinical specimens [4]. This case highlights a 68-year-old male with a deep wound infection in his right BKA site, in which cultures were positive for E. raffinosus.

Previous reports have linked E. raffinosus infections to the biliary tract, bacteremia, endocarditis, and vaginitis [5]; however, documented cases of deep wound infections caused by this organism are exceedingly rare. A literature review identified one confirmed case—a 2008 report of a patient with a decubitus ulcer wound infection caused by E. raffinosus, which exhibited resistance to all antibiotics except beta-lactams, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin [6]. Another study analyzing 49 cases of E. raffinosus bacteremia found that 81.6% originated from the biliary tract [5]. The current case contributes to the growing body of evidence by presenting a rare association of E. raffinosus with deep wound infections.

E. raffinosus infections have been associated with a 60-day mortality rate of 4.1% [5], indicating a necessity for early identification and intervention. This case underscores the importance of considering E. raffinosus in the differential diagnosis when deep wound infections are being evaluated. With the significant mortality rate, obtaining cultures upon initial presentation in the emergency department is crucial for prompt and targeted antimicrobial therapy. The exact source of infection in this patient remains unclear; however, several risk factors may have contributed. Examining the patient’s presentation above, the patient had multiple hospital admissions in the past year, resided in a nursing facility, and prior lower extremity procedures were performed—there are all significant predisposing factors that have contributed to the exposure of E. raffinosus. Recognizing these potential risk factors is vital when encountering E. raffinosus in clinical practice, particularly in patients with complex medical histories.

Conclusion

The case presented highlights a rare deep wound infection caused by Enterococcus raffinosus, emphasizing the importance of a thorough clinical evaluation. A good history is essential to identify possible risk factors for infection. The incidence of E. raffinosus continues to grow due to cross contamination, prior hospitalizations, and improper care in healthcare facilities. Early identification through bacterial sampling, adherence to proper wound care protocols, and timely antimicrobial treatment are critical in managing and preventing complications associated with this resistant organism.

REFERENCES

1.

Toc DA, Pandrea SL, Botan A, Mihaila RM, Costache CA, Colosi IA, et al. Enterococcus raffinosus, Enterococcus durans and Enterococcus avium Isolated from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Romania—Retrospective study and brief review. Biology (Basel) 2022;11(4):598. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

2.

Zhao H, Peng Y, Cai X, Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Huang H, et al. Genome insights of Enterococcus raffinosus CX012922, isolated from the feces of a Crohn’s disease patient. Gut Pathog 2021;13(1):71. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

3.

Said MS, Tirthani E, Lesho E. Enterococcus infections. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

[Pubmed]

4.

Sandoe JA, Witherden IR, Settle C. Vertebral osteomyelitis caused by Enterococcus raffinosus. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39(4):1678–9. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

5.

Lee YW, Lim SY, Jung J, Kim MJ, Chong YP, Kim SH, et al. Enterococcus raffinosus bacteremia: Clinical experience with 49 adult patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2022;41(3):415–20. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

6.

Savini V, Manna A, Di Bonaventura G, Catavitello C, Talia M, Balbinot A, et al. Multidrug-resistant Enterococcus raffinosus from a decubitus ulcer: A case report. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2008;7(1):36–7. [CrossRef]

[Pubmed]

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Acknowledgments

Verbal and written consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication submission.

Author ContributionsMarielle Roberts-McDonald - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Acquisition of data, Analysis of data, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Megan Brooker - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Shabnam Mansur - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Drafting the work, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Eugene Vitvitsky - Conception of the work, Design of the work, Revising the work critically for important intellectual content, Final approval of the version to be published, Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Guaranter of SubmissionThe corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Source of SupportNone

Consent StatementWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this article.

Data AvailabilityAll relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Conflict of InterestAuthors declare no conflict of interest.

Copyright© 2025 Marielle Roberts-McDonald et al. This article is distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original author(s) and original publisher are properly credited. Please see the copyright policy on the journal website for more information.